I think Kim Newman would agree with me when I say, “Once you go Drac, you never go back.” Or perhaps more accurately, “you might leave Drac, but you’ll definitely be back.” For my generation, there weren’t a lot of bloodsucking alternatives to the big D, aside from the Count on Sesame Street, or if you were older and not a Baptist, Warren Comics’ Vampirella. In the 70s, if you said “vampire,” people thought of Dracula, and “Dracula,” usually meant Bela Lugosi or Christopher Lee’s onscreen portrayal. I got my first copy of Dracula in grade four: Leonard Wolf’s annotated version. I never got past the first four chapters. Jonathan Harker’s story was riveting, but the Austenesque switch in voice to Mina Murray and Lucy Westenra writing about their love lives was lost on my pre-adolescent self. The illustrations by Sätty gave only a surreal window into the story’s later events.

As I grew up, more accessible options abounded: books like Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot and Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire; films like The Lost Boys and Near Dark. But when Francis Ford Coppola released Bram Stoker’s Dracula, I returned to Transylvania. Despite the film’s numerous digressions from the novel, my love of its visual splendor helped me finally finish the entire novel, finding to my surprise that final chase scene wasn’t a Hollywood addition. That same year, Kim Newman’s Anno Dracula hit the shelves, likely hoping to generate sales off the new film’s popularity, but somehow escaped my attention.

It wasn’t until beginning my steampunk research that I became aware of this wonderful piece of recursive fantasy, and I was thwarted in my first attempt to read it by some devious party, who had folded a space of some 70 missing pages together so well it escaped the notice of the used bookseller I purchased it from, and me buying it, until I turned page 50 or so and discovered the missing section. I tried soldiering on, but found myself somewhat confused, and abandoned the reading until I could find a complete copy.

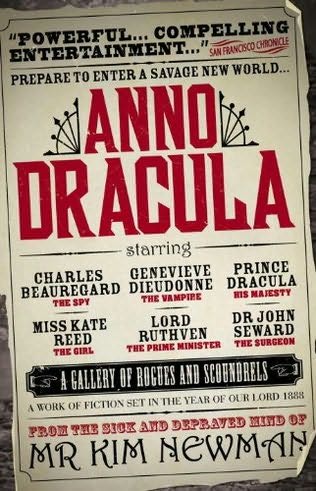

Finding a complete copy up until this past weekend was a formidable task. Paperback copies on the Internet sold at collector’s prices ranging from $50-200. With the rabid interest in vampires via Twilight, and the growing interest in steampunk, Anno Dracula was clearly an in-demand-but-out-of-print treasure. Neophytes and veterans of Anno Dracula can rejoice at the new edition released by Titan Books. Sporting the best cover I’ve seen of it yet, this lovely trade paperback boasts a number of extras, including annotations, the afterword from the paperback edition, the alternate ending from the novella version first printed in The Mammoth Book of Vampires, extracts from a screenplay treatment, an article called “Drac the Ripper,” and a short story set in the Anno Dracula universe, “Dead Travel Fast.” Unless you’ve been the most assiduous collector of Newman’s Anno Dracula works, this book offers a number of treats, even if you already own a previous edition. For those who have never read it before, it means you won’t have to pay through the nose to experience Newman’s wonderful alternative history of Stoker’s fiction world.

The premise is hardly original; any writer reading the line in Dracula when Van Helsing says, “if we fail,” to his vampire hunting companions has wondered at the counterfactual ramifications of those words. Stoker himself posits the outcome, and this speech is reprinted as an epigraph in Anno Dracula. What if good had not triumphed? What if Dracula had succeeded in securing a place on Britain’s foreign shores? Worse yet, what if he had somehow seduced the Queen, and become the Prince Consort of the greatest empire on the planet in the nineteenth century? Further, what would you call a man who murders the new citizens of this half-human, half-vampire Britain? A hero? A serial killer? Who then, is Jack the Ripper, if he’s only killing undead prostitutes? These are the questions that drive Newman’s story, and while others may have considered them, may even have written them, Newman, like Dracula, will continue to stand as a giant among many peers, given his encyclopedic knowledge of vampire lore, both literary and pop culture.

At one point, Lord Ruthven of John William Polidori’s The Vampyre, ponders who among his vampiric peers “has the wit to mediate between Prince Dracula and his subjects,” enumerating a global catalogue of famous vampires from Dracula’s penny dreadful antecedent, Varney, to soap-opera descendent, Dark Shadows’ Barnabas Collins. The universe of Anno Dracula is more than just a fantastical alternate history of the nineteenth century; it is a recursive fantasy that treats all vampire fictions as alternate histories. If Dracula exists, then so does Chelsea Quinn-Yarbo’s Saint-Germain. Newman is equal opportunity in this inclusivity: high or low-brow, if your bloodsucker was popular enough, she’s been included in Newman’s vampiric family tree. Anno Dracula is only the first in a series of books set in this alternate timeline, leading up to the forthcoming Johnny Alucard, which takes place in the 1970s on the set of Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula film. I suspect Titan will be releasing new editions of The Bloody Red Baron and Dracula Cha Cha Cha if sales of Anno Dracula go well.

Readers may wonder, as with any work of recursive fiction, do you need Newman’s encyclopedic knowledge of vampires, or even passing familiarity with Stoker’s Dracula to enjoy and appreciate Anno Dracula? To enjoy, no; to appreciate, yes. One could read the SparkNotes summary of Dracula and dive into Anno Dracula adequately prepared. Ultimately, an active reader could likely read Anno Dracula without any prior knowledge of Dracula and enjoy and comprehend Newman’s vision: he summarizes the requisite moments from Stoker to keep readers informed. However, this is a book that will reward either the reader with prior experience of Dracula, or the reader ready to engage in interactive reading. Like a good alternate history, Anno Dracula rewards the reader who steps outside the immediate page to enlarge their understanding of it. As a reader who teaches Dracula I found Newman’s treatment of Stoker’s characters, especially Arthur Holmwood turned Vampire, especially enjoyable: Holmwood’s privilege as aristocrat informs his initially selfish, but ultimately monstrous behavior, playing up the seeds of the character from Stoker. After all, what sort of man is capable of driving a stake through his former fiancée’s heart?

Speaking of Lucy Westenra, while she only appears in flashbacks and references, her journey is mirrored in the character of Penelope, fiancée to the male hero of Anno Dracula. Penelope’s character arc passes from society belle to newborn bloodsucker, but unlike Lucy, continues to provide a focalizing perspective of this experience. Dracula fans and scholars familiar with Stoker’s use of the New Woman will find Penelope’s character good grist for the academic paper mill. Dracula scholars looking to write something fresh should consider doing work on Newman’s Anno Dracula series.

Yet it is not simply Newman’s adherence to the minutiae of the greater vampire corpus that makes Anno Dracula appealing. In truth, this would only constitute grounds for recommending it to the most devoted of vampire fans. Anno Dracula, above all, is a hell of a novel. It’s a compelling read—not necessarily a page-turner. It’s not so much a book I couldn’t put down, but a book that kept seducing me to pick it up. Like Dracula, I kept coming back to Anno Dracula after spending time with other work or texts. Newman is no one-trick pony: from scene to scene, chapter to chapter, he switches his strategies. Consider this self-reflexively clichéd western-showdown-in-a-bar between 400-year-old vampire heroine Geneviève Dieudonné and Dracula’s Carpathian elite:

“She had seen a similar attitude a few years ago in an Arizona poker parlour, when a dentist accused of cheating happened to mention to the three hefty cattlemen fumbling with their holster straps that his name was Holiday. Two of the drovers had then shown exactly the expressions worn now by Klatka and Kostaki” (83).

This scene is exemplary of Newman’s ability to show, not tell, by using the display of Geneviève’s power and superiority to illustrate the difference in vampiric bloodlines: hers is purer than Dracula’s—she is kin to the beautiful vampires of Anne Rice with the strength and fighting capabilities of Vampirella. By contrast, the Carpathians, while formidable, share the “grave mould” of Dracula’s bloodline, which manifests in the ability to shape-shift into bestial forms, but is ultimately a wasting disease of sorts. This is Newman’s solution to the diversity of vampire forms in pop culture, and it is a brilliant, inclusive move.

Newman is not only interested in playfully reconciling the contradictions between Lestat and Orlock, but also incorporates the injustice of class and society in a world ruled by vampires. In addition to the courtly vampires of Ruthven and Holmwood, there are bloodwhores: prostitutes and addicts in Whitechapel and Old Jago. Newman does one better than many steampunk writers playing with these sites of squalor by playing a Dickensian card in the form of Lily, a child-turned-vampire in violation of the law. She is sickly, left to fend for herself, hiding from the sun under dirty blankets. Her fate is tragic, based in character, evoking the strongest emotional reaction of any in Anno Dracula. Her fate, more than anything else, demands the climactic confrontation with the big D himself, a scene that demands a date to begin principle shooting.

It is also the scene that contains the most overt homage to Dracula as the King of all Vampires, even if here he is only Prince Consort. These little moments of fictional fealty are scattered throughout the novel, sometimes achieving a sort of pop-commentary on Dracula-copycats, such as Count Iorga, but this last one strikes me as Newman’s thesis for Anno Dracula. I’ll include only enough to make my point, leaving the literally gory details for you to enjoy when you read it yourself:

“Prince Dracula sat upon his throne, massive as a commemorative statue His body was swollen with blood, rope-thick veins visibly pulsing in his neck and arms. In life, Vlad Tepes had been a man of less than medium height; now he was a giant.” (411)

In the introduction to Leslie Klinger’s brilliant New Annotated Dracula (which would provide a perfect accompaniment to Anno Dracula, as Klinger’s annotations treat Stoker’s epistolary narratives as actual historical documents), Neil Gaiman states that “Dracula the novel spawned Dracula the cultural meme.” In a little over a century, Dracula has gone from semi-successful novel to the second-most-filmed character in the world. Dracula is to the vampire what New York or London is to the city. We may have our romantic dalliances with Edward Cullen, or divert ourselves with the hyper-violent undead addicts of Blade II, or the virus-styled plague victims of Matheson’s I Am Legend. But in the end, all these lead back to Dracula as the vampire who looms largest, like Castle Dracula over the surrounding countryside: Kim Newman’s Anno Dracula renders this ruling spectre a reality, in a London that never was, but in a world we’re very interesting in visiting. If your summer requires some shade, or better yet shadow, slap on the sunscreen, put on the shades, and sit down on your beach towel to enjoy one of the best pieces of vampire fiction we’ve had since Stoker himself set down the words, “How these papers have been placed in sequence will be manifest in the reading of them.” These words are true of Anno Dracula as well, a wonderful pastiche of vampire trivia, historical speculation, and thrilling mystery and adventure.

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.